Pamela’s story

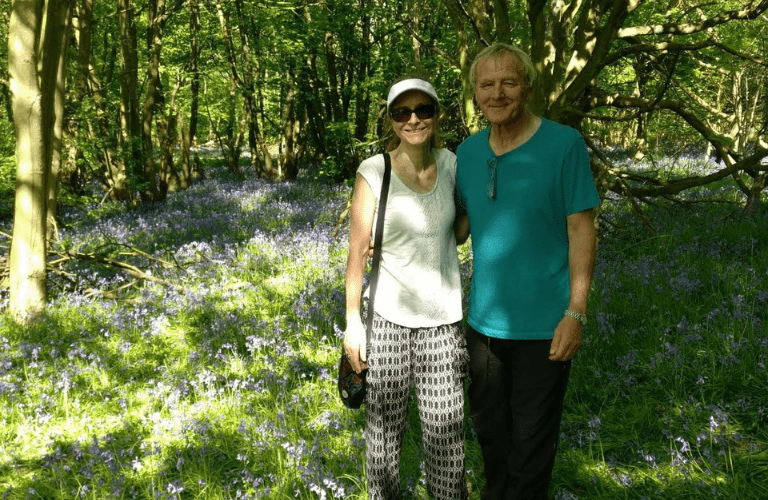

When Pamela applied for NHS continuing healthcare for her husband Rob, she felt the odds were stacked against them from the outset.

Alzheimer’s disease is the most common form of dementia. It is thought to be caused by a build-up of proteins in the brain which affect how the brain cells transmit messages. As time passes, more brain cells are damaged, leading to worsening symptoms.

This page, written by our dementia specialist Admiral Nurses, explores the symptoms, causes and possible treatment of Alzheimer’s disease.

Alzheimer’s disease is a type of dementia that mostly affects older adults, but it can also develop in younger people under the age of 65, when it is known as ‘young onset Alzheimer’s disease’. It causes problems with memory, thinking and behaviour. As a progressive condition, it will affect more and more aspects of a person’s life over time.

There are many different forms of dementia, all of which are progressive conditions that cause damage to the brain.

Unlike other types of dementia, Alzheimer’s disease is thought to be caused by the abnormal build-up of two proteins in the brain, ‘amyloid’ and ‘tau’. These form structures called ‘plaques’ and ‘tangles’, which damage the brain cells. Alzheimer’s disease also reduces the levels of chemical messengers in the brain (‘neurotransmitters’) which makes it harder for messages to pass between brain cells.

As Alzheimer’s disease progresses, brain cells continue to die and parts of the brain shrink, and the levels of neurotransmitters decrease further.

Different forms of dementia have different symptoms, but in Alzheimer’s disease, the most common early sign is difficulty with memory.

Alzheimer’s disease is the most common form of dementia, affecting one in 14 people over the age of 65, and one in six people over the age of 80.

It can also affect younger people and is the most common form of young onset dementia (where symptoms develop before the age of 65).

It can be helpful to think of dementia progressing in three stages – early, middle and late stages.

The most noticeable early sign of Alzheimer’s disease is usually difficulty with memory, especially short-term memory. The person might:

Other early symptoms may include:

In the early stages of Alzheimer’s disease, the symptoms may be mild, but they can still be extremely frustrating for the person and those around them, especially if they do not understand why the changes are happening.

In the middle stages, symptoms may include:

In the late stages of Alzheimer’s disease, new symptoms may develop, including:

Alzheimer’s progresses gradually; however, each person’s experience is different and it is impossible to predict how quickly they will deteriorate.

Getting an accurate diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease as early as possible is important, as treatments to help slow its progress tend to be most effective in the early stages. A timely diagnosis also means support can be put in place to help maintain the person’s quality of life.

There is currently no cure to stop or reverse the disease.

There are a number of causes and risk factors for Alzheimer’s disease. Some are unavoidable, but others could be reduced through lifestyle changes. Some of the causes include:

Age is the biggest risk factor for developing Alzheimer’s disease. The older someone is, the more likely it becomes, but it can also occur in younger people under the age of 65.

Some health problems can raise the risk of getting Alzheimer’s disease. These include heart and blood vessel issues such as high blood pressure and diabetes as well as obesity. People with learning disabilities, particularly Down’s syndrome, are also more likely to develop Alzheimer’s disease.

In rare cases, Alzheimer’s disease is caused by a genetic fault that runs in families, but this accounts for fewer than 1% of all people diagnosed with the condition. Alzheimer’s disease is more likely to be inherited in people whose parents developed the condition at a very young age.

Read more about genetic forms of dementia.

Women are slightly more likely to develop Alzheimer’s disease than men, and there is some evidence that people from African-Caribbean and South Asian backgrounds may be more at risk.

Although age is the biggest factor for Alzheimer’s disease, studies suggest that the way we live can also influence our chances of developing this and other forms of dementia. Here, we list some of the lifestyle factors that could increase the risk.

A diet high in processed foods, sugar and unhealthy fats may increase the risk of Alzheimer’s disease because it can lead to conditions that affect the heart and circulatory system (cardiovascular conditions) and reduce blood flow to the brain.

The risk of developing these conditions and others than are linked to dementia can be reduced by eating a healthy, balanced diet. The NHS Eatwell Guide can help you understand which foods to eat to improve and maintain your physical and mental health.

There is also a link between alcohol and developing dementia so it’s important to keep drinking within the recommended limits.

A lack of regular exercise can contribute to the risk of developing Alzheimer’s disease, as well as other forms of dementia. Exercise improves heart health and helps blood flow and oxygen delivery to the brain, which supports cognitive function.

Smoking increases a person’s risk of developing dementia by damaging blood vessels and reducing blood flow to the brain. This can increase the risk of Alzheimer’s disease. Some studies show that smoking increases the risk of developing dementia by 30-50% but quitting smoking, even later in life, can reduce the risk of cognitive decline and improve overall brain health.

It’s thought that a lack of sleep, or poor quality sleep, can lead to a build-up of proteins in the brain, which may increase the risk of Alzheimer’s disease. How much each person needs will vary, but six to eight hours’ uninterrupted sleep is ideal for most people. The NHS has information on improving sleep.

Although there is no guaranteed way to prevent Alzheimer’s disease, certain steps may help reduce the risk:

It may take several appointments and tests over a number of months to get a diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease. This is particularly true for younger people, who typically face a much longer wait to get a diagnosis than older people.

If dementia is diagnosed early, there may be more treatment options, and support can be put in place sooner.

The first port of call if you are worried about symptoms of Alzheimer’s disease in yourself or someone else is the GP. They will rule out any underlying physical or mental health issues that may be contributing to the symptoms, many of which can be treated. These include depression, anxiety, vitamin deficiency, diabetes, hormonal conditions or menopause. They will ask the person:

It is a good idea to keep a record of symptoms, triggers and how they affect the person to show the GP. The GP should carry out some simple physical tests, such as a blood pressure check, and refer the person for blood tests. They may request an ECG (a check of heart rhythm) and a brain scan.

A short memory and concentration test (often known as the ‘mini mental state examination’) should be carried out by a GP as part of the assessment. This may include:

If the tests rule out other conditions that may be causing the person’s symptoms, the GP should refer them to a specialist memory clinic for more detailed assessments. These may be carried out by a nurse, psychiatrist, neurologist or elderly care specialist.

The person may also have further scans such as an MRI or CT scan – these produce detailed images of the brain and may show changes associated with Alzheimer’s disease or other conditions.

It is a good idea to prepare for the appointment to ensure you get the most out of your time with the healthcare professional.

Find out how to best prepare for a GP appointment.

There is currently no cure for Alzheimer’s disease. However, for some people, medication can improve the symptoms and slow its progression.

The main medications for Alzheimer’s disease are donepezil, rivastigmine and galantamine. These work by increasing the levels of a chemical called acetylcholine in the brain, which helps the brain cells communicate with each other. They are only effective in the early to middle stages of Alzheimer’s disease, and they depend on the person being physically fit and well, and able to remember to take the medication at the same time each day.

Another medication, called memantine, may be prescribed for moderate to severe Alzheimer’s disease, or if the person cannot tolerate the other treatments.

CST is a type of therapy that involves taking part in activities to improve memory, language skills and problem-solving abilities. It often takes place in a group, which can also provide opportunities to socialise and share experiences, but may be offered one-to-one. The memory clinic will be able to tell you if this is available in your area.

This involves working with a specialist – usually an occupational therapist – along with a family member or friend to find ways to manage particular tasks, such as using a mobile phone or cooking a meal. The aim is to get the parts of the brain that still work well to help the parts that do not. It can also be personally satisfying to accomplish a task that the person finds difficult.

Many people with Alzheimer’s disease have difficulty with short-term memory, but longer-term memories may remain intact for some time. Reminiscence and life story work focus on skills, achievements and happy memories, and can improve mood and wellbeing.

Reminiscence work involves the person talking to a family member, friend or professional about their past, often using prompts such as photos, music or favourite possessions.

Life story work involves compiling a record of the person’s life, for example:

On average, people with Alzheimer’s disease live four to eight years after diagnosis, but some can live as long as 20 years or more. The life expectancy for people with Alzheimer’s disease varies widely depending on many factors, including age and the stage of the disease at diagnosis, other medical conditions and overall health.

It is impossible to predict the exact length of time someone may have; instead, focus on maintaining quality of life/enjoying time together rather than speculating how long they may have left.

As Alzheimer’s progresses, damage to the brain affects critical functions such as breathing, mobility and swallowing. This can lead to complications like falls, infections such as pneumonia, and malnutrition. Many people with Alzheimer’s disease become increasingly frail and are unable to recover from these complications.

Living with Alzheimer’s disease can be difficult for the person with the diagnosis and those around them, especially as the symptoms progress. These tips may make living with the condition easier:

While the symptoms of Alzheimer’s disease always worsen over time, a good routine and support network can help the person with the diagnosis maintain their independence and quality of life for as long as possible.

Some common misconceptions about getting a diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease are:

While these things are likely to happen as dementia progresses, people in the early stages of Alzheimer’s disease may be able to continue with many of their usual activities with minimal changes.

Read Sylvia’s story"Alzheimer’s is a bully. It constantly tries to take things away.But I don’t want to be defined by this bully. Instead, I try to think of Alzheimer’s as a different entity that has come to walk alongside me. It’s one I have learnt to live with. If I keep fighting it and never accept it, I don’t think it’s a fight I can win. If I live alongside it, there’s a degree of separation between the woman I am and always have been; and Sylvia with Alzheimer’s."

If you need information or support around Alzheimer’s disease or any other aspect of dementia, you can speak to a specialist Admiral Nurse on the free Dementia Helpline on 0800 888 6678 (Monday-Friday 9am-9pm, Saturday and Sunday 9am-5pm) or email helpline@dementiauk.org.

If you prefer, you can book a phone or video appointment with an Admiral Nurse.

When Pamela applied for NHS continuing healthcare for her husband Rob, she felt the odds were stacked against them from the outset.

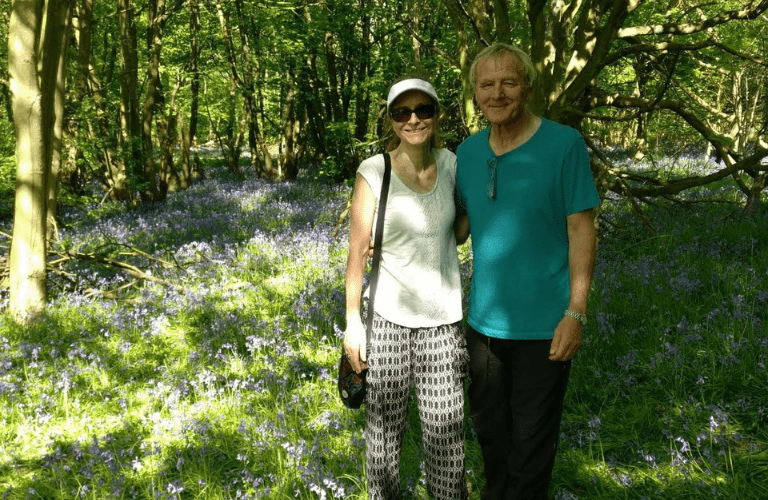

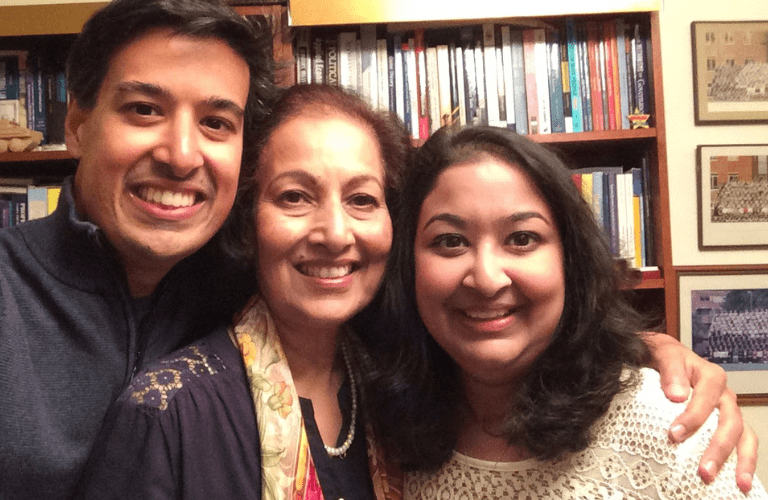

Brother and sister Aqib and Shahbanu share their story of how they support each other through their mother’s dementia.

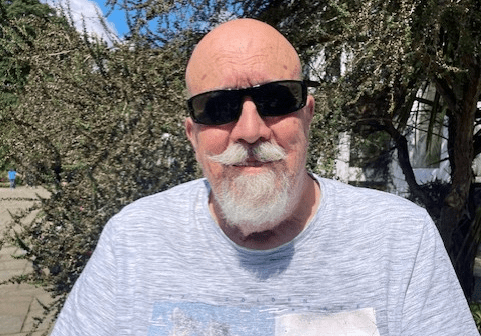

Peter shares how his specialist Admiral Nurse has encouraged him to live well with dementia – including by learning to fly an aeroplane .

About 1% of all people diagnosed with dementia carry a ‘deterministic’ gene, which means the carrier will almost certainly develop dementia, but this is a very rare genetic fault. Some people carry a ‘risk’ gene or genes (called APOE4), which means they are at risk of developing Alzheimer’s. Some people carry one copy of the risk gene, and some may have two. Having one or two copies of ‘risk’ genes will increase your risk of developing dementia (usually Alzheimer’s disease) but this is not inevitable.

There is no guaranteed way to prevent Alzheimer’s disease, although certain steps may help reduce the risk, including stopping smoking and reducing your alcohol consumption to within the recommended limits. You should make sure to take any medication prescribed for diabetes, heart conditions, depression and other physical/mental health problems alongside having regular health checks, including blood pressure and blood tests.

A balanced diet, regular exercise, getting 6-8 hours uninterrupted sleep and staying mentally active can also help reduce the risk.

People with Alzheimer’s disease can have hallucinations, but they are more common in people with dementia with Lewy bodies and Parkinson’s.

There is currently no cure for Alzheimer’s disease. However, for some people, medication can improve symptoms and slow the progression.

When someone is diagnosed with dementia, they are legally required to inform the Driver and Vehicle Licensing Agency (DVLA) in England, Scotland and Wales or the Driver and Vehicle Agency (DVA) in Northern Ireland. It does not automatically mean they will have to give up driving straight away, although this is a possibility. Read more about driving and dementia.